KILL THE VIRUS, NOT THE GOOSE

Joey A. Bermudez

Chairman, Maybridge Finance

May 19, 2020

When business owners ask for a lift, they are making a very reasonable request.

The best way to appreciate their predicament is to understand the revenue cycle of a typical enterprise. I call it the “cash to cash” cycle.

Every enterprise starts with a certain amount of assets. These assets are then deployed in production or service delivery to create more valuable assets. If you are a restaurant, you use cash to buy fish, meat, vegetables, ingredients and cooking supplies to create meals that you can price at reasonable profit. If you are a tour bus operator, you use cash to hire bus drivers and intelligent guides to conduct tours that make the bus ride interesting. Along the way, the cash assumes other asset forms – from raw materials to goods in process to finished products to receivables – until they get converted back to cash, hopefully at amounts greater than the cash with which you started.

The length of this cash cycle depends on the type of enterprise. If your enterprise is a wet market stall, your cash to cash cycle is probably one day. If your enterprise is housing construction, the cash to cash cycle is way longer than a year.

When you are prevented from carrying out your business, as in an abrupt lockdown, your cash to cash cycle is interrupted. There is damage arising out of the business interruption. The amount of damage depends on the stage at which you are in the cash to cash cycle just before the interruption. If the cash cycle was interrupted before you could commence a new production or service delivery cycle, you are stuck with cash which you cannot not deploy. If the cash cycle was interrupted before your production or service delivery cycle was completed, you are stuck with an unfinished contract which may never get completed. If the cash cycle was interrupted after you have delivered to your customer but before you could collect payment from him, you are stuck with a receivable which is at risk of not getting collected.

What happens when the cash cycle freezes? I cringe whenever non-entrepreneurs and armchair analysts oversimplify the problem. They naively argue that when the business stops for two months, the revenue lost is just 2/12 or 16.7%% of its annual revenue. They’re missing the point. Whenever the cash cycle is interrupted for a significant length of time (and two months is definitely “significant”), the entire working capital of the business is put at risk. There emerges the possibility that the entrepreneur might lose the entire business.

What happens when you stop a business or even an economy in the middle of its production cycle? The assets stranded in the production process can become totally worthless. If you were in the catering business and had procured supplies to prepare an exquisite dinner for a 200-person convention and the event gets cancelled at the last minute because of the lockdown, would those supplies be worth anything at all by the time you resume operations? When the economy reopens, do you think it will be business as usual for businessmen? Of course not. Re-starting a business is often many times more difficult than starting a new one because you are carrying baggage from the past.

When the economy reopens, the big task for the entrepreneur is to assess the damage. It is like inspecting your house the morning after a very strong typhoon.

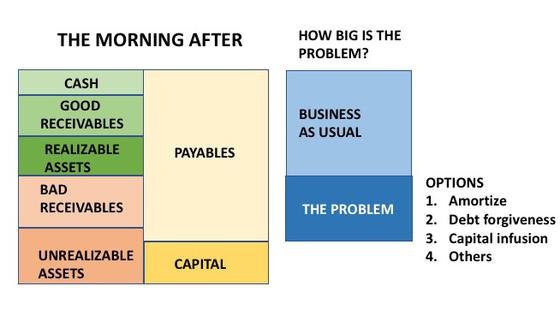

On the other side of your balance sheet are your payables and capital: the yellow boxes. You can see from the illustration that the good assets (the green boxes) are no longer enough to settle the liabilities (the light yellow box) because some assets became uncollectible or unrealizable. The light blue box on the right tells you the extent to which the entrepreneur can re-start the business. The dark blue box represents the working capital that has become stranded because it is no longer supported by good assets.

It is obvious that the amount of cash that will re-circulate in the business after the crisis has considerably shrunk. It is also obvious that the entrepreneur needs to deal with payables that cannot be settled in the current operating cycle because of the shrinkage of the business. Again, the dark blue box represents the baggage that the entrepreneur has to carry going forward.

What should the entrepreneur do with this dark blue box?

He needs to engage with his creditors. He has four options.

Firstly, he can convince his creditors to stretch out the repayment of these liabilities (represented by the dark blue box) over a longer period, hopefully long enough for the business to generate surplus profits annually that can go into repayment of this debt.

Secondly, he can ask for full or partial debt forgiveness. Is this an unusual request? Yes, it is. But remember that the Covid19 crisis is an unusual event that has brought about an extraordinary situation. Extraordinary problems call for extraordinary solutions. Countries and nations have asked for, and were granted, debt forgiveness in various forms. I recall that in the aftermath of the 1998 crisis, some of the country’s largest conglomerates defaulted on their debt and later, using conduits, bought back these debts at deep discounts. That is debt forgiveness no matter how you look at it. These companies continue to exist today and they continue to enjoy the respect of the business community.

Thirdly, he can get rid of the problem once and for all by drawing on his personal resources to infuse more capital into the company and liquidate the dark blue box. Only a small number of business owners have this capability today.

Fourthly, there are options that might open up to him if and when the stimulus programs being discussed today at executive and legislative levels see the light of day.

How successful the entrepreneur will be in pursuing these options will depend on his relationship with his creditors. From my experience, it is important for the entrepreneur to make the bank understand that the latter is better off keeping the enterprise alive by bending over during these extraordinary times than killing the business altogether by tightening the noose. Trite as it may sound, the saying that one should not kill the goose that lays the golden egg was probably never truer than today.